The Americans with Disabilities Act has enabled several members of my family to participate fully in all aspects of their education and employment and in public accommodations.

What’s of particular interest and importance is access to public accommodations, including telecommunications, TV, movie theaters and websites. All are fundamentally essential to being able to participate in and enjoy the benefits of life in the 21st century. Imagine, if you will, how different and possibly difficult your life would be if you could not search the internet for information, post a message on social media to your friends or check your bank statement online.

The U.S. government and the courts have found access to telecommunications, TV, movies and websites all to be public accommodations in that they each are services that are available to the public, and as such, must also be made available to persons with a range of disabilities.

One of the aspects that attracted me to my current role at Roostify over 18 months ago as general counsel and chief compliance officer was the fact that I would be able to work with the digital mortgage engagement platform for people with physical and visual limitations. All companies should endeavor to comply with the ADA by at all times being 100% compliant with the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines on both desktop and mobile devices.

Sounds easy, right? Hardly.

The U.S. Department of Justice has never issued regulations on web content compliance

Although the ADA was enacted in 1990, the Justice Department has never published regulations specifying what it takes for a website to be ADA compliant. To be fair, website and mobile devices didn’t exist when the ADA was passed. However, the Justice Department has had plenty of time since to promulgate regulations to give businesses and employers guidance about what their obligations are. In fact, it was as recent as 2017 that the Justice Department abandoned its effort to draft regulations on the accessibility of web-based content.

An international standard, the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines become the de facto means by which compliance with the ADA is measured in the U.S.

Nature—and courts—abhor a vacuum. In the absence of website accessibility regulations from the Justice Department, the Web Accessibility Initiative of the World Wide Web Consortium, the primary international standards organization for the internet, has since 1999, published guidelines on website accessibility under the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines. Courts in the U.S. have started to adopt WCAG as the standard for measuring website accessibility, providing a welcome measure of clarity. Interestingly, in many other parts of the world, the WCAG standards are the law, such as in the European Union and Canada.

The latest iteration of WCAG, WCAG 2.0 is based on four principles: perceivability, operability, understandability and robustness.Underlying each of the principles are guidelines, and underlying the guidelines are the criteria for determining whether a website meets the standard.

The W3C also publishes techniques for meeting WCAG 2.0’s guidelines and success criteria. The published techniques are guidance rather than requirements. And as you might imagine, the techniques evolve with the changes in technology, whereas the principles, guidelines and success criteria remain unchanged.

The principles are designed to make web content accessible, “to a wider range of people with disabilities, including blindness and low vision, deafness and hearing loss, learning disabilities, cognitive limitations, limited movement, speech disabilities, photosensitivity and combinations of these. Following these guidelines will also often make web content more usable to users in general.”

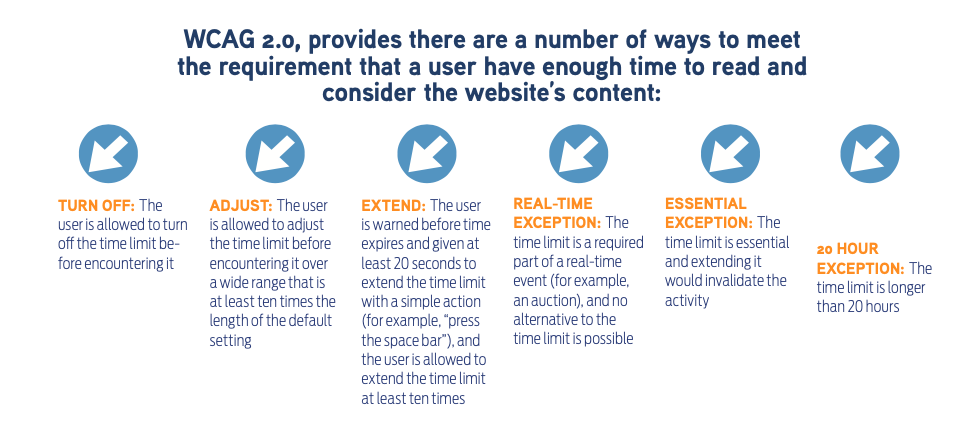

This means, for example, that text alternatives are available for visual images such as photographs, and that there’s at least a 7:1 contrast ratio between text and images so a user with a visual impairment can access the material, even if the use of assistive technology, such as a screen reader, is necessary. Or that sign language interpretation is provided for pre-recorded audio. Or that all functionality is available by use of a keyboard rather than solely by use of a mouse, and that the website’s “time-out” functionality is configurable to enable a user with a physical limitation to have adequate time to read and consider the website’s content.

The guidelines in WCAG 2.0 are not immutable. That is, the guidelines recognize that there are alternatives provided when a principle can’t be achieved using one technique but can be achieved using another or even an assistive technology. For example, as discussed above, the operability principle can be met by use of a keyboard and a configurable time-out functionality.

WCAG 2.0 has three levels of conformance to the success criteria specified for each guideline: A, AA and AAA, each building on the prior level. There are five conformance requirements: level of conformance (A, AA and AAA); conformance achieved for a full web page, such as any video content being equally as accessible as text; all web pages that are a part of a process – think about a restaurant reservation booking site – conform; assistive technologies, such as a screen reader, used to make content accessible; and technology that isn’t accessible doesn’t prevent a user from accessing parts of the website that are accessible.

WCAG 2.0 compliance isn’t something that requires a massive undertaking; in reality, it requires a thoughtful approach to the web content development process to ensure the standard is being met.For example, for people with visual impairments—including people who are blind, have limited vision or are colorblind—the following should be considered in development of a desktop or mobile application to satisfy WCAG guidelines:

Color coding and contrast: There should be adequate contrast between the color of the font and the page so the text is easier to read. Also, multiple color schemes should be available for users to pick the one that they can see best.

Alternate image text: Images or videos on the site should have descriptive text attached to them. This allows screen readers to read that text, which then describes the image or video out loud.

Descriptive titles, headers and links: All pages should have unique titles and headers, and all hyperlinks should have unique anchor text that is descriptive of the associated information. Headers should also be formatted with heading style designations instead of changes in font, color, or size. Hyperlinks should be underlined.

Flexible text size: Users should be able to change the font size on a page, do not hardcode the size of the text on website pages.

Text, instead of images, for important information: Do not convey critical information with images; always use text, so text-to-speech programs can read it aloud. If there is an important image or graphic, always include alternate text or description.

Screen reader accessibility: Design web pages so information can be read by screen readers and text-to-speech programs. Links, lists and headers should be clearly identified with descriptive, non-generic terms.

Zoom functions: Users should be able to use the zoom feature on the site, both on the desktop and on a mobile device. Do not disable zoom functionality on either version of the website.

You’ll likely note that many of these accessibility features contribute to a high-quality user experience even for a user without any visual impairments.

Why lenders care about compliance with WCAG

So the details of WCAG compliance may or may not be of interest to the ordinary user, but to mortgage lenders, compliance with WCAG is of paramount importance. Why? Not just to avoid legal liability, but also to make their offerings available to the widest range of customers possible.

This only makes economic sense. For example, in New York, California and Florida, three of the most populous states, nearly a million people have a visual impairment that is not overcome by the use of corrective lenses. Add to that the millions of people who are also color blind, and you have a meaningful number of people who would find it difficult, if not impossible, to apply for a mortgage online if accessibility were not designed into the platform.

Lenders need a detailed process for ensuring the accessibility of a cloud-based platform. First, they should have trained developers on WCAG compliance principles, guidelines, success criteria and techniques, with an emphasis on techniques. The developers should be trained to ensure that the basics of the platform are compliant, as well as ensuring that any configurable options, such as colors and fonts, meet WCAG requirements.

The training should also include compliance with a browser-based version of the platform, as well as the version accessible using a mobile device such as an iPhone or iPad. It should be periodically refreshed to ensure that the latest techniques are addressed. Lenders should also perform rigorous in-house quality assurance reviews before lenders make updates or upgrades to ensure that the platform remains compliant.

And third, companies should bring in a third-party auditor to periodically review thier platform to assess their conformance with the applicable requirements, and provide a certification of their compliance with using a Voluntary Product Accessibility Template. Always strive for 100% compliance.

I talk with a number of our customers about Compliance programs, including WCAG compliance. From these talks, I’ve learned that many lenders are only now fully grasping why 100% WCAG compliance matters:

- They have seen the dramatic and sustained increase in lawsuits brought under ADA Title III, which is the key section in the ADA pertaining to website accessibility. Title III bars discrimination “on the basis of disability in the full and equal enjoyment of the goods, services, facilities, privileges, advantages or accommodations of any place of public accommodation by any person who owns, leases (or leases to) or operates a place of public accommodation.”

- They have become aware of state anti-discrimination laws such as California’s Unruh Act, under which a person who can demonstrate that they were discriminated against on the basis of a disability, may receive $4,000 in statutory damages for each incident where they suffered discrimination.

- And they have seen courts apply the WCAG 2.0 standard to websites. For example, in the recent case of Robles v. Domino’s Pizza, the Ninth Circuit held that the ADA applied to Domino’s Pizza’s website and mobile app, in part because Domino’s also had a physical presence, and that in the absence of regulations by the Justice Department, WCAG Level 2.0 was the standard for measuring accessibility. The Supreme Court denied Domino’s appeal of the Ninth Circuit’s decision, leading me to believe that the Robles decision is law. The next issue will be whether ADA Title III applies also to websites and apps for businesses that have only a virtual presence and no physical locations.

In the end…

Because of the ADA, and in particular Title III, members of my own family have been able to participate fully in this vibrant, ever-changing economy. Seeing how they’ve benefitted has made me even more passionate about ensuring everyone has the highest standards of accessibility. It’s not only the right thing to do legally and economically, it’s simply the right thing to do.