#div-oas-ad-article1, #div-oas-ad-article2, #div-oas-ad-article3 {display: none;} If you work for Google or Facebook, company perks might include gourmet lunches, community gardens, napping pods, and even “adult play areas.” With this kind of environment at work, how can home compete?

Well, if you live in Silicon Valley and are one of the region’s numerous millionaires or even billionaires, thanks to a ton of recent tech company IPOs, bringing the perks home is easy.

Take Facebook COO Sheryl Sandberg, for example. She owns a 9,000-plus-square-foot mansion in Menlo Park, and much of that square footage underground. Her basement reportedly includes a basketball court, wine room, and, oh, a waterfall.

Perhaps that’s nothing compared to her boss, Mark Zuckerberg, who bought a whole neighborhood around his Victorian home in Palo Alto to create a personal buffer zone.

“Technology is the driving force in real estate values in this area,” said Yvonne Broszus, MAI, director at Valbridge Property Advisors in San Jose. “Companies here are growing rapidly. And they are bringing in a highly educated, highly paid workforce.”

A workforce with stock options.

Kurt Reitman, principal at The Reitman Group in Menlo Park, said he believes the increase in IPOs is actually “driving residential values” in Silicon Valley. A lot of newly rich professionals who have cashed in on their stock options are buying homes with cash or with minimal financing because their actual salaries are not commensurate with the cost to traditionally finance a home purchase, at least not a home purchase in Silicon Valley.

The average price of a Silicon Valley home in 2015 was $870,000. In San Francisco, it was $1.1 million. For comparison’s sake, the median home value in 2015 in Austin was $290,700.

A history of low supply and high demand

With prices so high, is this a smart place to buy a home or invest in residential real estate? The market has to burst at some point, right?

Well, not if history is any indication.

According to Matt Regan, senior vice president, government relations, of the Bay Area Council, California’s real estate values have been “out of whack” with the nation at large since the early ’70s. He notes the average home price in coastal California is two-and-a-half times the national average. Combined with the fact that the Golden State generates 10 times as many jobs as housing units, you’ve got a clear recipe for home-price inflation.

In fact, while the rest of the nation was going through the Great Recession, Silicon Valley barely missed a beat. “No one expected recovery to be this swift or this large,” added Regan.

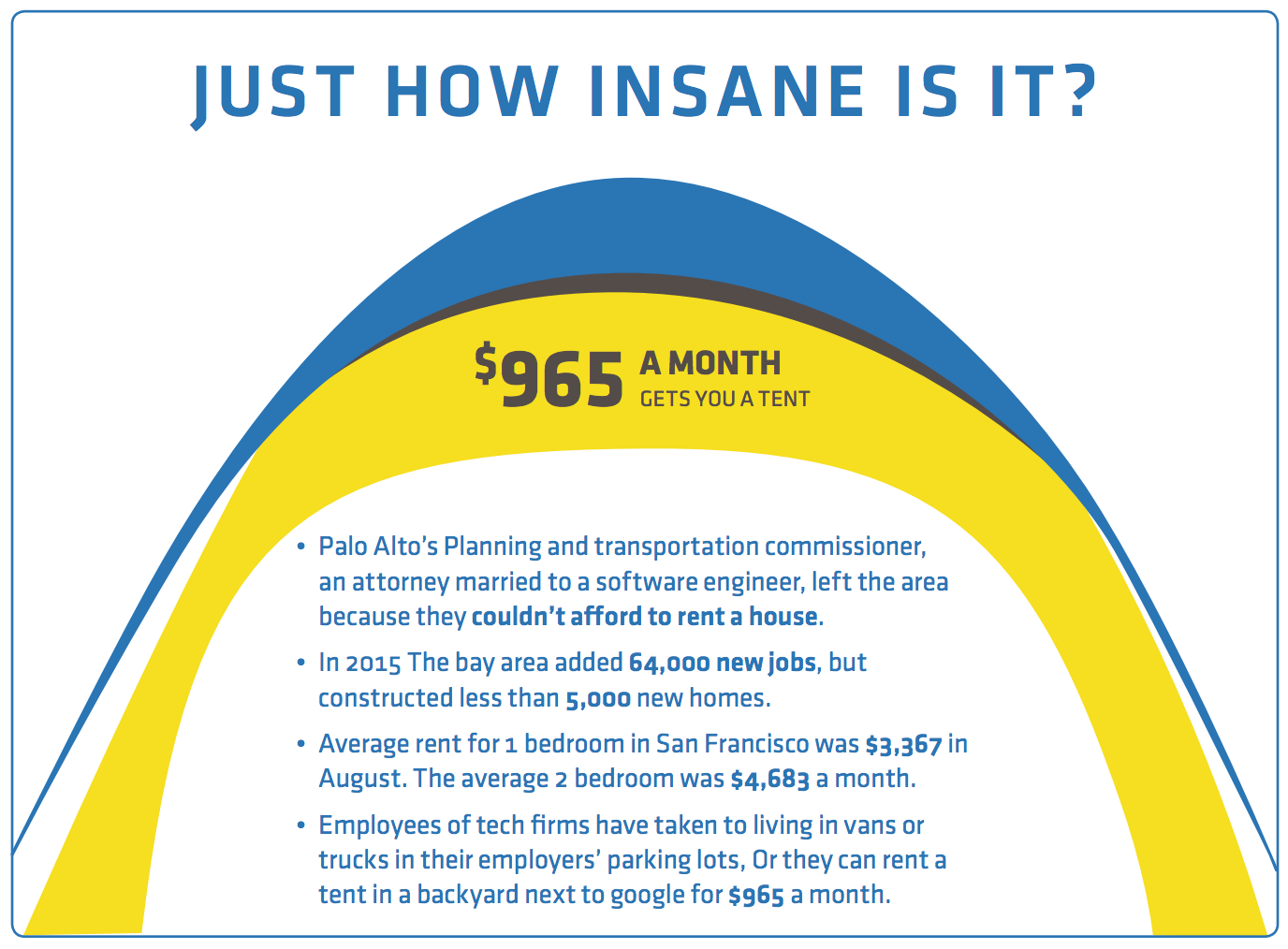

According to the California Employment Development Department, the city of San Francisco, along with the counties of San Mateo and Santa Clara, added 385,000 new jobs to the local economy between 2010 and 2015. However, the localities only issued building permits in that same period for 58,324 units, not even enough for half the new influx of workers.

Gene Williams, MAI, vice president at CBRE in San Jose, pointed out that while Silicon Valley has traditionally garnered about a third of the nation’s venture capital, it’s now reeling in about 50%, and half of that is in software development.

The market really started to boom, in Broszus’ view, in 2011 and 2012, and it’s been going strong ever since. Homeowners who sold residences in 2015 in the San Francisco metro area realized a 65% gain in price appreciation from when they purchased, according to RealtyTrac. Surrounding Bay area  counties saw similar gains.

counties saw similar gains.

With insufficient supply to meet demand, the result is not only over-the-top real estate prices but severely clogged highways, as 170,000 daily commuters drive from distant (and more affordable) bedroom communities into the Bay area.

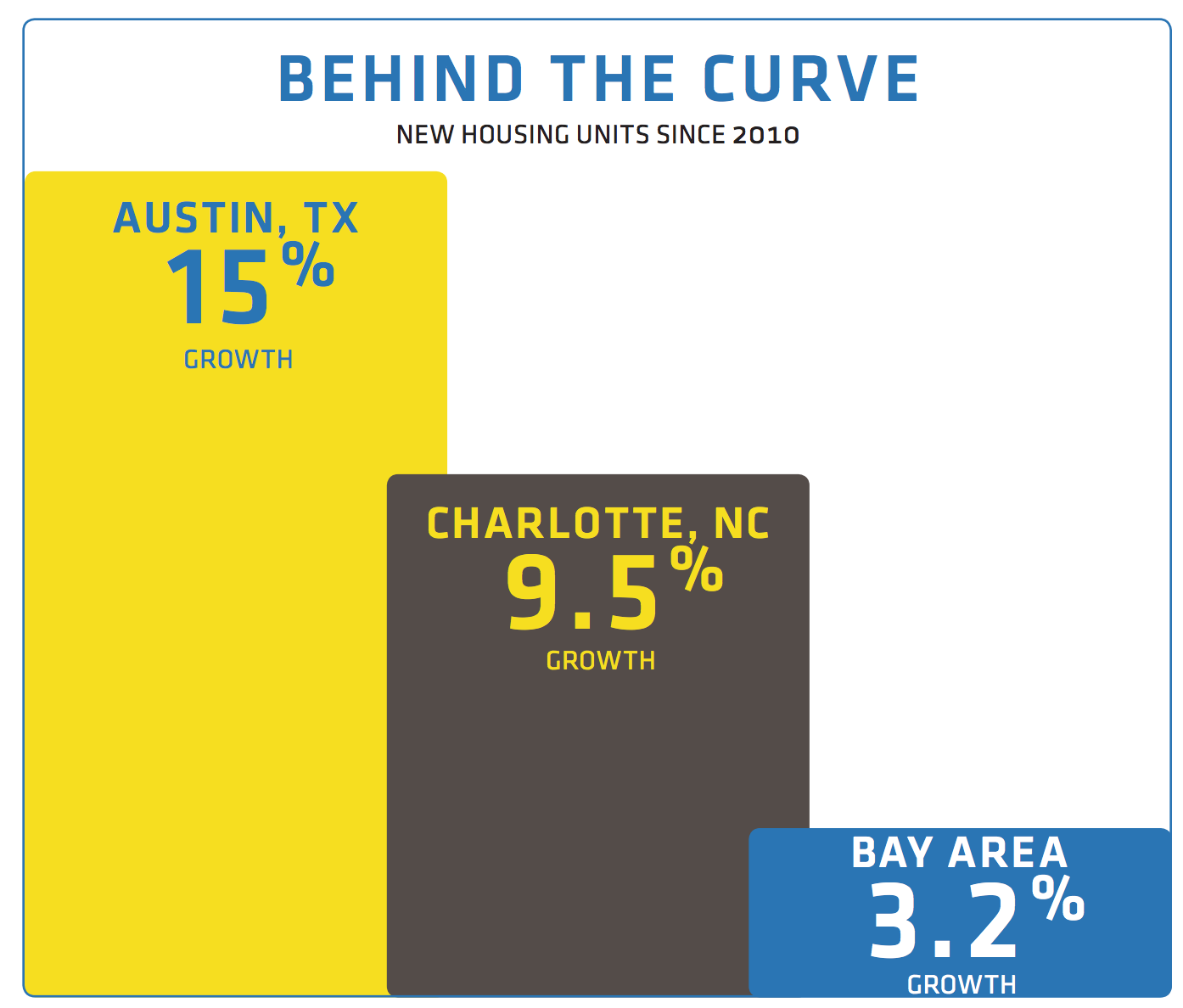

Regan pointed out that California is way behind the curve in supplying needed new housing. Since 2010, the Bay area has permitted development of 88,000 housing units, representing a 3.2% increase in growth.

Meanwhile, in other hot tech markets, housing supply is coming online much more quickly. Austin has seen 15% growth in the same period, and Charlotte, N.C., has experienced 9.5% growth. “Our growth is anemic compared to other major economic competitors,” he added.

“The current system is not sustainable,” Regan warned. “Any healthy community needs a broad stock of housing. The people who bag our groceries need a place to live, too.” Because the lack of housing and even greater lack of affordable housing in Silicon Valley is so dire, Regan said he knows school teachers who are living four and five to an apartment. “I also know a firefighter who commutes to the Bay area from Reno, Nevada.”

Why is it so hard to get new housing online in Silicon Valley?

One reason is the state’s ambitious climate goals, Regan said.

“Ironically,” he added, “40% of greenhouse gases are being caused by traffic.” So much for saving the environment by limiting housing growth.

“We’re not moving the needle on climate goals,” said Regan, in large degree because of the very environmental restrictions that limit growth in housing stock while forcing growth in commuter traffic.

#div-oas-ad-article1, #div-oas-ad-article2, #div-oas-ad-article3 {display: none;} Crisis or Opportunity?

Unsurprisingly, some of the hottest housing growth areas, according to Broszus, have been near public transportation hubs or at least proposed hubs now that the Bay Area Rapid Transit is in full expansion mode.

The first phase of the extension to Berryessa is scheduled for completion by the end of 2017, and construction will begin on an extension through downtown San Jose in 2019.

“Over the last five years, there has been a lot of focus on office space near the rail corridor because a lot of young professionals prefer to live in San Francisco,” Reitman explains. They want to use rail to get to their jobs in a region rife with traffic issues. To cope with traffic problems in the absence of rail, many large corporations actually use buses to transport their employees from home to work and back again.

“Cities are starting to require that new residential development have at least 50 to 60 units per acre,” Broszus explained, as municipalities struggle to deal with limited available land in the face of exploding growth.

With so much new money flowing into the area and the exit of the unskilled labor force that worked in the region’s once-dominant manufacturing industry, “there is now an imbalance i n the economy,” according to Broszus. Lower income workers are beginning to make an exodus and seeking employment in other big growth areas, like Texas, where housing prices aren’t so out of control.

n the economy,” according to Broszus. Lower income workers are beginning to make an exodus and seeking employment in other big growth areas, like Texas, where housing prices aren’t so out of control.

“It’s becoming a crisis,” Broszus said. The result is that local governments are now requiring new development or redevelopment projects to include affordable housing options in order for the developer (in many cases big names like Google and Facebook) to obtain project approvals.

In Fremont, for example, homebuilder Lennar is working on a new development project that will result in more than 2,200 new housing units and 1.4 million square feet of commercial space. To gain project approval, however, Lennar’s project had to include 286 “affordable” housing units, according to The Mercury News.

Reitman is quick to point out that “affordable housing does not mean low cost housing” in Silicon Valley. The lowest home price sale in Menlo Park in 2016 stood at $802,000, based on data through May.

And while Broszus wouldn’t go so far as to say Silicon Valley is filled with “one-percenters,” she said, “as far as who is owning the Valley, I would say ‘yes,’ it’s definitely the one-percenters.” She added, however, “The extremely wealthy still need service industry workers.”

Where are those workers going to live? It’s anybody’s guess.

“The housing imbalance we have isn’t just due to housing not being affordable,” Broszus said. “It’s not available either.” She said for every three workers in the city of Palo Alto, there is only one residence.

As a result of the housing shortage and growing awareness of how it impacts both the region’s service industries as well as the environment, Regan said recent polls in California show a slight increase in support among existing residents for creation of in-fill housing. “Politics around new housing in California are toxic,” he added. “The Central Valley has now become acres and acres of subdivisions.”

How Silicon Valley companies are coping

Companies are pre-leasing new developments, before they’re even complete, to reserve residential space for their workers. Demand is well in excess of supply, both on the residential and commercial side. Last winter, Mountain View’s city council approved plans for a dense housing project and received solid support for it from Google.

It’s no wonder.

Hired.com noted that the average software engineer’s salary in San Francisco is $132,000. While a comparable role in places like Seattle and Houston pays less, when one takes the cost of housing into consideration, a software engineer’s salary in Seattle becomes the equivalent of $164,000 in San Francisco. In Houston, the lower cost of living would make that engineer’s salary equivalent to $195,000 in San Francisco!

In Santa Clara County alone, there is more than 12 million square feet of office space currently in development. “Six years ago, rents were so low, no one would have conceived of constructing an office building,” Williams said. “Now we’re seeing a giant influx of office demand.”

The highest demand in the commercial arena is for Class A office space for high-tech companies, mainly in areas like Palo Alto, Mountain View, and Sunnyvale, where rents have skyrocketed.

The further south or north from these areas one goes, the lower the rents. Yet vacancy rates have dropped across the whole market.

According to the San Francisco Center for Economic Development, the city’s rental rate per square foot for Class A office space closed out 2015 at $72.26, surpassing even Manhattan. “The domino effect is forcing up office demand in adjacent areas,” Reitman said.

For example, Apple is now finished with its new headquarters in Cupertino.

The growth isn’t restricted to IT, however. Bioscience is also big in the areas around Stanford University and the University of California-Berkeley.

With no more room in Palo Alto and other hot areas, values are spiking everywhere. Mountain View and Sunnyvale are prime examples. In March 2015, DivcoWest acquired 210,000 square feet of office space in San Mateo for $130.6 million ($621 per square foot). Owner JPMorgan originally acquired the property in 2007 for $100.5 million.

Meanwhile, in Sunnyvale, Divco sold an office complex to CBRE Global Investors for $29.5 million after having purchased the property only two years earlier for $18.8 million, according to the San Jose Business Journal.

#div-oas-ad-article1, #div-oas-ad-article2, #div-oas-ad-article3 {display: none;} What It All Means for Investors

Reitman says the extreme upward movement in rental rates from San Francisco to San Jose has resulted in cap rate compression. “But it’s difficult to document cap rates due to the lack of transactions,” he said. “There is a definite lack of supply, and when transactions do occur, they reflect significantly higher per-unit values.”

Williams said the result is that cap rates have dropped as much as 300 to 400 basis points in some areas. “That gives huge property value jumps.”

At the close of the second quarter of 2016, office vacancy rates decreased 20 basis points in San Francisco to 6.5%, according to a recent market report from Colliers. The rate was 7.07% for San Mateo County, the lowest vacancy rate in 15 years.

One would think the cycle of high demand and short supply would eventually end, leading to a localized bubble in Silicon Valley in the future. And some companies are starting to see the light. Oakland-based Jamba Juice, for example, is moving to Texas; Western Digital is leaving for Oregon; and Intel  has moved most of its chip manufacturing to Oregon. Regan said the moves have been driven by companies’ desire to be in locations where skilled workers can actually afford to live.

has moved most of its chip manufacturing to Oregon. Regan said the moves have been driven by companies’ desire to be in locations where skilled workers can actually afford to live.

According to a recent report from the Silicon Valley Competitiveness and Innovation Project, the region lost more residents to other parts of the U.S in 2014 than it gained. That hasn’t happened to Silicon Valley since 2011. The report also showed that between August 2014 and August 2015, home prices increased by 13% and rents by 12%.

Is it any wonder some people — and companies — have started leaving, and does this mean a bubble is looming?

Regan doesn’t think so. He noted the housing bubble that launched the last recession was caused by speculation and rental prices that were out of step with purchase prices. “Right now, rental and purchase prices are aligned, and both sets of prices are rising pretty fast and equally,” he said.

That said, the current pace of price appreciation is reflective of a lack of supply. “Companies are going to reach a breaking point because it’s too expensive for people to live here,” Regan said.

The Bay Area Council is lobbying for an array of options to increase housing, particularly, affordable housing. Regan said the council is pushing for easing in the permitting process for “penny flats” — accessory housing built by current homeowners such as over-the-garage apartments or remodeled basements to accommodate a renter.

“If just 10% of homeowners built them, that would mean 150,000 units of new housing.” The State Senate recently approved SB1069, which would reduce permitting barriers on accessory housing, but it still has to go through the state assembly.

Regan is quick to point to success stories. Thirty-five percent of homes in Vancouver, he said, have accessory housing units. “It’s like invisible in-fill,” he explained, and it requires no public subsidy.

Meanwhile, both Santa Clara and Alameda have initiatives on their ballots for $950 million and $580 million, respectively, for general obligation bonds to build affordable housing. “But raising money through traditional bonds takes years,” Regan said.

Public support is necessary, however, as “the free market only produces luxury products because that’s the only product they can sell and make a profit,” he added.

Right now California Gov. Jerry Brown is proposing a bill to fast-track projects that meet all local zoning, planning, and design requirements and would provide 2% of units as “affordable” or 10% if adjacent to public transportation. But Regan is quick to note that the environmental community is “a heavyweight force” against the governor’s proposal.

“We can’t create a bifurcated state, where the wealthy live along the coast and the rest live in the Central Valley,”

Regan said.

But if California legislators don’t act more quickly, that’s exactly what’s going to happen.