Which of the too-big-to-fail megabanks didn’t actually require a capital injection during the financial crisis, even though Treasury Secretary Henry Paulson eventually forced it anyway? If you answered Wells Fargo & Co. (WFC) — that banking behemoth rooted in the cornhusks of Iowa, of all places — you’d be correct.

Wells Fargo has a reputation among investors as a conservatively run bank whose approach allowed it to steer clear of much of the riskier aspects that drove many of its competitors near to, or completely over, the ledge in the run-up to the financial crisis of 2007-2009.

But that was then. This is now. And now is about the death of the mortgage refinancing business, a huge driver of Wells Fargo’s revenues in the post-crisis period; in fact, Wells Fargo had surpassed Bank of America to become America’s lender, funding more mortgage volume than any other large commercial bank in the country in 2012 and 2013.

With the refi boom now over, what’s next? Is Wells Fargo still a good bet — or has the time come to look elsewhere?

THE BULL CASE

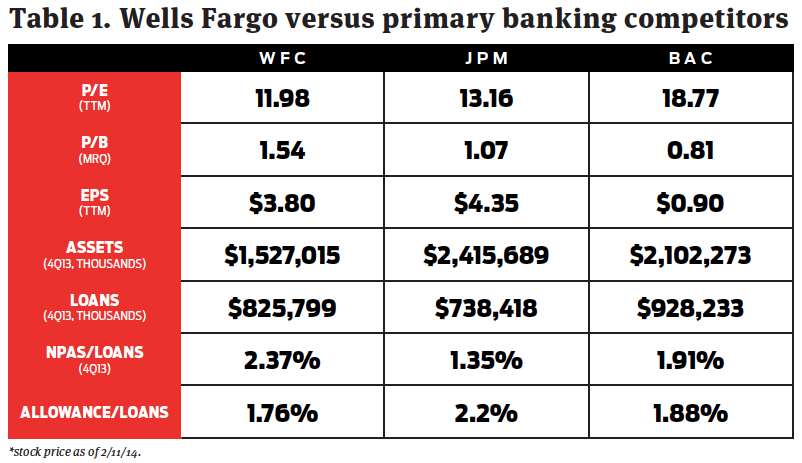

If you’re investing in banks, you’re looking for the safe and stable money. And that’s where Wells Fargo shines — with a price/book value that’s almost double that of Bank of America, for example, it’s clear that investors understand the difference between the two banks and are voting accordingly.

So should you.

While the bank did see net interest margin (NIM) decline 12 basis points to 3.26% in the fourth quarter of 2013, this decline came as the bank increased cash and deposit holdings as a function of regulatory liquidity requirements under Basel III.

The single greatest way a well-run bank can fight ongoing NIM pressures is by building loan balances up while carrying low-cost deposits.

And Wells appears to already be doing just that: HousingWire. com reported on February 6 that the bank dropped its minimum FICO requirement on FHA-backed loans to 600 from a previous floor of 640. It’s clear the bank is already aggressively looking to grow its loan base, even as refinancing activity dries up.

This means Wells Fargo is doing something the other major banks aren’t: returning to the non-super prime lending space, a welcome move and an area that has largely remained underserved in the wake of the financial crisis.

Investors in WFC stock are poised to ride the bank’s leading move into this space, as executives at the bank have repeatedly stressed to HW that they are more than willing to find ways to lend outside of the QM box imposed by Dodd-Frank legislation earlier this year.

This isn’t a rogue opinion, either. It’s shared by major analysts such as those at FBR Capital who said in a recent report that they “expect high purchase volumes to support origination activity going forward, which bodes well for the resilience of mortgage banking [at Wells Fargo] through the rest of this year and next.”

THE BEAR CASE

That incredible price-to-book ratio that investors have rewarded Wells Fargo with? It’s actually a strong reason not to invest, as there just isn’t any upside to the stock relative to some of its ostensibly lesser competitors.

If anything, this means the stock is too expensive against its peers — and doubly so, when you take time to consider that Wells Fargo continues to carry much more meaningful exposure to bad loans on its books.

Wells Fargo’s non-performing assets as a percentage of loans are a whopping 102 basis points above JP Morgan Chase & Co. (JPM), and 46 basis points above levels at Bank of America (BAC).

And to make matters a little more foreboding, Wells Fargo has reserved 12 basis points less than Bank of America for losses against its loans; and it’s reserved an eye-opening 44 basis points less when compared to JP Morgan Chase.

As an investor, you need to ask yourself: is Wells Fargo that much better at making loans, so that even its non-performers are materially different in loss experience versus other major banks?

That’s a tough pill to swallow in its own right, because loans tend to be loans.

But it’s a nearly impossible pill to swallow when considering the rich valuation already awarded to WFC relative to its banking brethren.

And if that weren’t enough, consider this, too: Wells Fargo’s business is far more exposed to lending activities than its competitors. More than 50% of the bank’s asset base at the end of the fourth quarter in 2013 was represented by loans; those numbers were 40% and 30% at Bank of America and JP Morgan, respectively.

This means that Wells Fargo is going to have to get more aggressive in lending in order to maintain revenues, a trend we’re already seeing take shape as they lower FICO score thresholds.

And that means increasing exposure to riskier and riskier loans — at a bank that already holds far less in reserve for its non-performing assets than any of its primary competitors.

Is that a bet you really feel like placing?